Part II : Shrinking Neural Networks for Embedded Systems Using Low Rank Approximations (LoRA)

Code Follow Along

The code can be found in the same tensor rank repository :

https://github.com/FranciscoRMendes/tensor-rank/blob/main/CNN_Decomposition.ipynb

Convolutional Layer Case

The primary difference between the fully connected layer case and the convolutional layer case is the fact that the convolutional kernel is a tensor. We say that the number of multiplications in an operation depends on the size of the dimensions of the tensors involved in the multiplication. It becomes critical to approximate one large multi-dimensional kernel with multiple smaller kernels of lower dimension.

Working Example

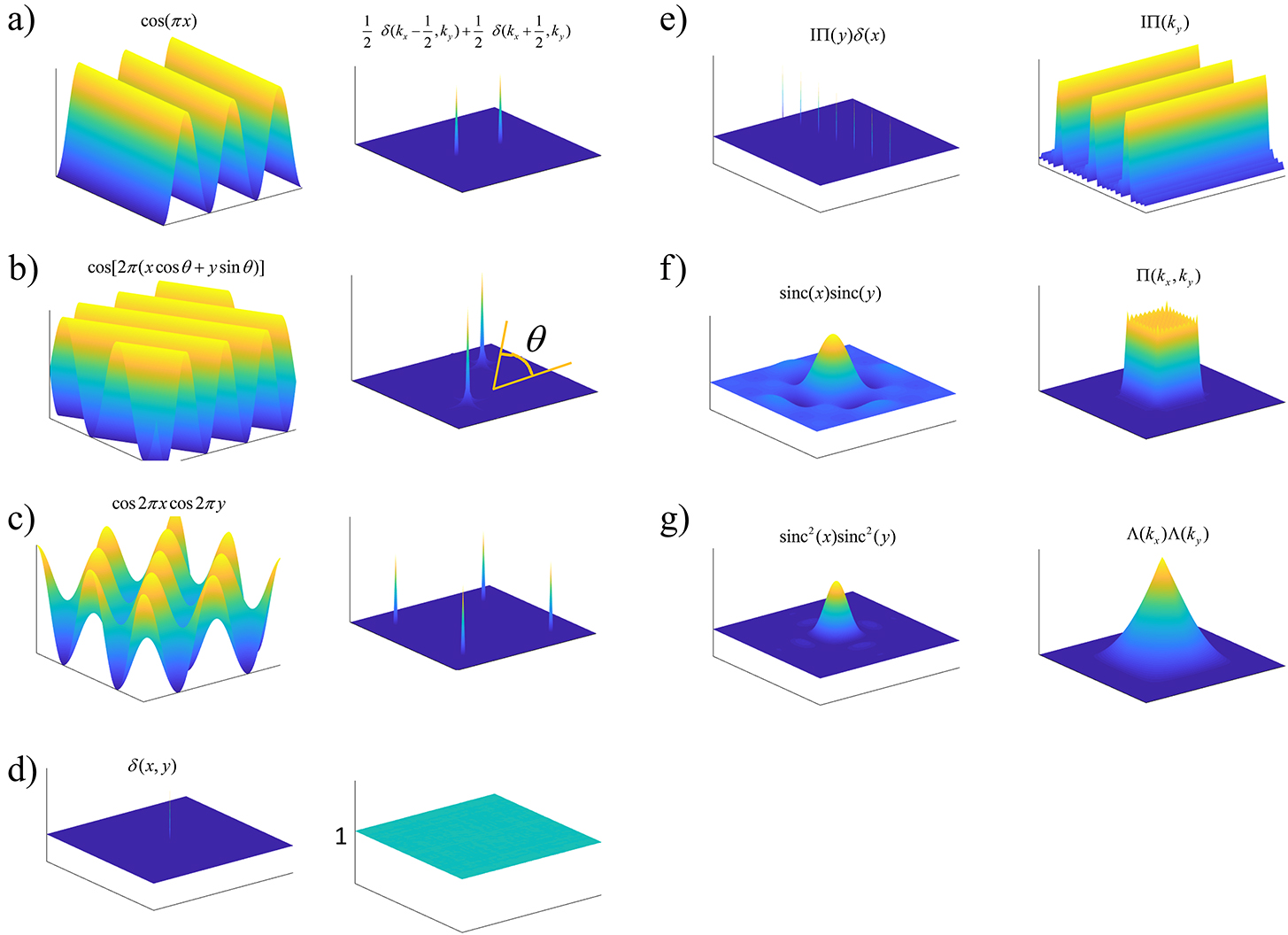

A convolution operation maps a tensor from one dimension to a tensor of another (possibly) lower dimension. If we consider an input tensor

Using similar logic as defined before, the number of multiplies required for this operation in

This is similar to the case of the SVD with an important difference the core

The number of multiplies in this operation is

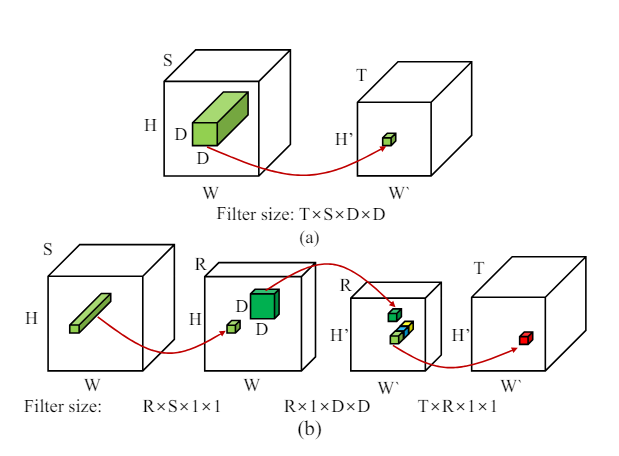

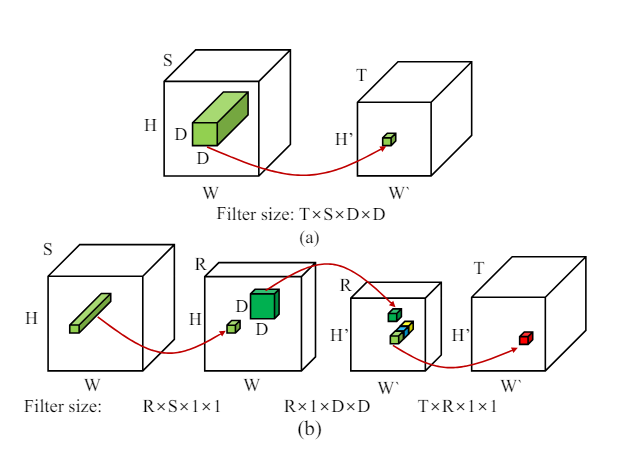

In the figure above each of the red arrows indicates a one convolution operation, in figure (a) you have one fairly large filter and one convolution, whereas in the figure (b) you have 3 convolution operations using 3 smaller filters. Let’s break down the space and size savings for this.

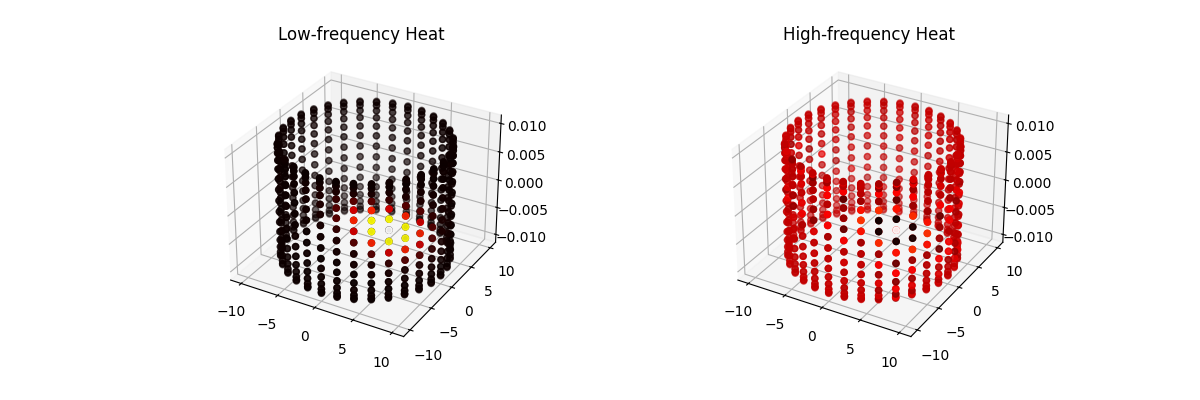

Rank Selection

So we are ready to go with a decomposition, all that remains is finding out the optimal rank. Again, if the rank is too low we end up with high compression but possibly low accuracy, and if the rank is too high we end up with very low compression. In embedded systems we need to be quite aggressive in compression since this can be a hard constraint on solving a problem. In our previous example, we could "locally" optimize rank but in the case of CNNs this is not possible since at the very least we would have at least one FC and one convolutional layer and we must compress both somewhat simultaneously. Brute force quickly becomes hard, as for even modest tensor combinations such as

Naive Rank Selection Algorithm

The intuition is that if a layer is more sensitive to decomposition it should have higher ranks. Our algorithm is proprietary but the intuition is as follows. We start with a rank of 1 and increase the rank by 1 until the accuracy drops below a certain threshold. We then decrease the rank by 1 and continue until the accuracy drops below a certain threshold. We then take the rank that gave the highest accuracy. This is a naive algorithm and can be improved upon.