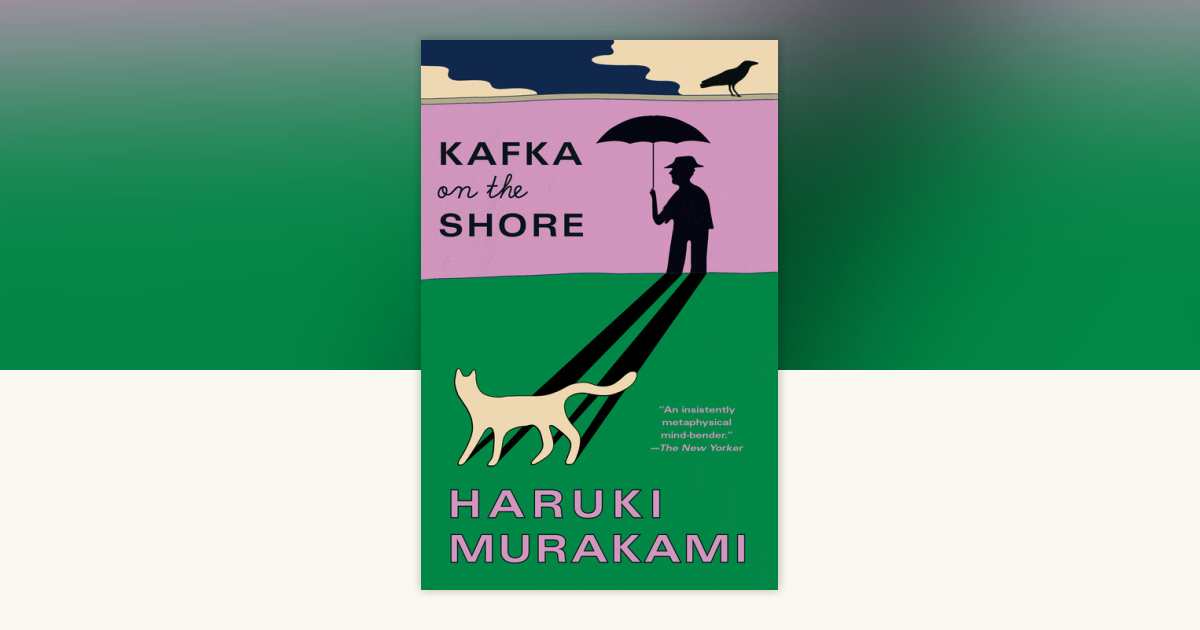

Book Review : We - Evgeny Zamyatin

It is hard to write this book review without overusing superlatives. Widely regarded as the inspiration for both 1984 and Brave New World, this book serves as the template for revolution in a dystopian world ruled by an all-encompassing police state. Written during the early years of the Soviet Union, it holds the dubious distinction of being one of the first (if not the first) books to be banned by the Communist Party.

I’ve been on a bit of a Soviet literature tear lately, and this book has been on my list for some time. I’m probably not the target demographic for most modern science fiction, but this book is so much more than that.

Plot

The translation conveys an enthusiastic, eager, albeit halting and fragmented tone. This accurately reflects D-503’s (the protagonist’s) hurried journal entries, which form the chapters of the novel.

The book is set in 2600 AD, just after the 200 Years War (a war to end all wars), which concluded with the formation of One State, a totalitarian regime where everything, including sex, follows a fixed schedule regulated by a complex network of bureaucracies.

Refreshingly, for a science fiction novel, the protagonist is not unhappy with the status quo—he embraces and enjoys it. The One State aligns with his ideals of order, method, and rationality. Everything changes when he meets and subsequently falls in love with I-333.

While both 1984 and Brave New World feature similar female characters, the sexual attraction of I-333 is but a small facet of her complex appeal to D-503. She represents a curve in his life of straight lines and right angles. She is a violation of the order he holds so dear, yet he finds himself irresistibly drawn to her.

Major Themes

The obvious metaphors of One State to the Soviet police state are compelling, as are D-503’s eulogies to their necessity and importance in daily life. This is a significant difference to most dystopian fiction that often reflects the downsides of dystopia but none of their motivating factors. Here we have the diary and journal entries of a true believer, we are treated with extensive philosophical insight into why One State exists and why it is good.

“The only means of ridding man of crime is ridding him of freedom.”

The idea that elimination of freedoms is the only way to rid man of crime is a recurrent theme in the book, of the many references to Christianity in this book, I found this to be the most compelling. Religion (and personal morality) only exists when there is freedom, without freedom there is no need for personal morality. Which is why One State was so successful, it obviated the need for religion, by eliminating all personal freedoms.

In the modern Western world, we often take it for granted that individual freedoms are the most basic right. This book asks the reader to challenge that idea substantively via conversations with I-333. One of the less understood ideas of communism is the importance of the collective, an idea almost incomprehensible to those educated primarily in Western philosophy. There is a scene in HBO’s Chernobyl where hundreds of workers scrape the top of the Nuclear plant of radioactive debris in what seems to be an irrational disregard for personal safety all for the greater good of the Soviet Union that captures this sentiment, this book re-iterates that theme across many different mundane freedoms, such as the right to privacy, right to procreate and the right to choose how to lead one’s life.

“We comes from God, I from the Devil.”

The above quote captures that sentiment better than the scene from Chernobyl does. It is interesting that Zamyatin chose this particular turn of phrase, but it corresponds to an idea in the Eastern Orthodox church that faith can only exist as a collective not as an individual.

When referring to belief in God, “I” is almost never used in the Orthodox Church. That is why there is no “I believe in God”, there is only “we believe in God”, in Orthodox prayer.

This theme often occurs in juxtaposition with another one, the contrast and similarity between religion and science. This is directly at odds with most of what we now experience in the West. Science and Individual Freedom are the core tenets of most modern societies, however, Zamyatin portrays these ideas as fundamentally in conflict with each other. To One State, science would measure every aspect of the human experience, and make cold blooded calculations of cost and benefit. And remove the benefit at any cost. What does it matter if one life is lost as long as the lives of countless others are preserved? Science allows us to measure everything, why not the human experience? Gradually the belief in the Science of One State obscures its rationale and assumptions.

“knowledge, absolutely sure of its infallibility, is faith”

And that a move away from the safety and comfort of rational science is a nightmare to him

“Now I no longer live in our clear, rational world; I live in the ancient nightmare world, the world of square roots of minus one.”

In addition, to the philosophical metaphors the books is rife with references to mathematics in the form of the Taylor and Maclaurin series, which form part of the broader mathematical narrative that is woven around life in One State. This is still relevant almost a hundred years after the book was written, the desire to quantify and measure the human experience is something innate to those who seek to mimic how science is applied to other more tangible fields.

Summary

I left this book with a greater appreciation for the randomness and disorder inherent in human beings, and how that is our defining characteristic. Modern capitalist societies can benefit from redistribution through centralization and a stronger sense of community. However, this book offers valuable insight into the dangers of excessive centralization. The fact that the Soviet State remains the only large-scale implementation of communism and serves as the inspiration for One State is a humbling reminder that the economic Left is vulnerable to a complete lack of freedom, even when successful in achieving its overarching ideals. Often, the line between utopia and dystopia is blurred. It seems fitting that my next review could very well be Westad’s The Cold War.