Locality, Learning, and the FFT: Why CNNs Avoid the Fourier Domain

Introduction

Convolution sits at the heart of modern machine learning—especially convolutional neural networks (CNNs)—yet the underlying mathematics is often hidden behind highly optimised implementations in PyTorch, TensorFlow, and other frameworks. As a result, many of the properties that make convolution such a powerful building block for deep learning become obscured, particularly when we try to reason about model behaviour or debug a failing architecture.

If you know the convolution theorem, a natural question arises:

Why don’t CNNs simply compute a Fourier transform of the input and kernel, multiply them in the frequency domain, and invert the result? Wouldn’t that be simpler and faster?

This blog post addresses exactly that question. We will see that:

FFT-based convolution is not local.

In the Fourier domain every coefficient depends on every input pixel. This destroys the locality structure that CNNs rely on to learn hierarchical, spatially meaningful features. As a result, it breaks the very inductive bias that makes CNNs effective.FFT-based convolution is not computationally cheaper in neural networks.

Although FFTs are asymptotically efficient, they must be recomputed on every forward and backward pass—and the cost of repeatedly transforming inputs, kernels, and gradients outweighs any benefit from spectral multiplication.

By the end of this post, we’ll have a clear, explicit comparison—both in matrix form and via backpropagation—showing why CNNs deliberately perform convolution in the spatial domain. Any practioner of signal processing should also be interested in knowing when the “locality” property is useful and when it is not!

1-D Convolution

Let us start with the most basic form of convolution, the 1D convolution. In this case you have a filter (which is nothing but a sequence of numbers) that you want to multiply with your signal in order to produce another signal which is hopefully more interesting to you. For example, in your headphones, you want to multiply a set of numbers with the music signal such that the resulting signal is more music than the wailing baby 1 row behind you.

1 | import numpy as np |

Convolution Theorem

This brings us to the convolution theorem wherein we can prove that the process of convolution i.e. multiplying window-wise h and x is mathematically equivalent to a simple multiplication between the fft of h and the fft of x.

1 | def conv_via_fft(x,h): |

2-D Convolution

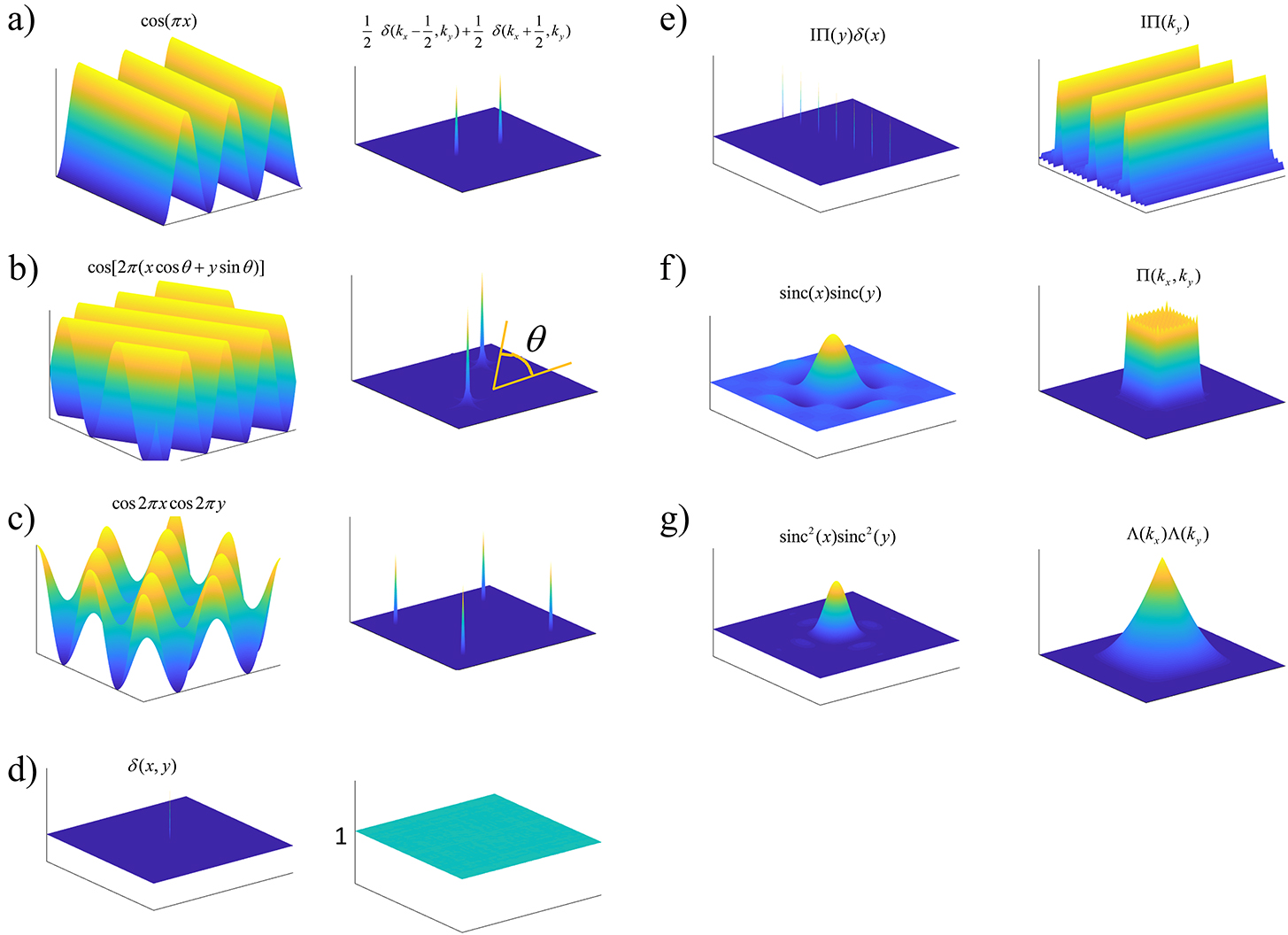

Just like before before we will convolve a 2D filter with a 2D signal in the spatial domain. We will then, try to do it using the FFT. We will verify that the convolution theorem does indeed work in the 2D space as well.

1 | def conv2d_direct(img, ker): |

Convolution Theorem 2D

In a similar way to the 1D case instead of windowing and multiplying, we can take the fft of the signal and the kernel and simply multiply.

1 | def conv2d_fft(img,ker): |

So why do NNs not use the FFT?

In a neural network, convolution is used to generate feature maps that feed into the next layer. At first glance, the convolution theorem suggests a tempting shortcut: instead of sliding a kernel spatially, we could transform both the image and kernel into the frequency domain, multiply them element-wise, and transform the result back. The output would be mathematically equivalent—so why not do this inside CNNs?

It turns out there are two fundamental reasons:

Neural networks care about more than just the output—they care about how the output is produced.

During backpropagation, each filter weight is updated using gradients derived from local spatial features. This locality enables CNNs to learn hierarchies of edges, textures, shapes, and patterns.

In the Fourier domain, however, gradients flow through global Fourier coefficients. Every frequency component depends on every pixel, so the update for a single weight depends on the entire image. This destroys the spatial locality that CNNs rely on and eliminates the inductive bias that makes them effective.The FFT is not “simpler” computationally for neural networks.

While FFTs are efficient in isolation, a CNN would need to repeatedly compute forward FFTs, spectral multiplications, and inverse FFTs—not just for the forward pass, but also for backpropagation.

When you count actual multiplications and transforms, the FFT approach is often more expensive, especially for small kernels (e.g., 3×3, 5×5), which dominate modern architectures.

In short: CNNs avoid the Fourier domain because it removes locality and adds computational overhead—both of which undermine the very reasons convolution works so well in deep learning.

2D Spatial Convolution as a Matrix Multiply

For our next trick we will show the exact way in which your hardware actually computes convolutions. Spoiler: it will be some kind of matrix multiplication. This is quite different from the way convolution is taught in the classroom where you usually convolve with a patch of pixels in the spatial domain and roll the kernel onto the next patch nearby. In reality, this whole process is just represented as one huge matrix multiply. It is very important to think about convolution in this way, as it makes approaching complex questions easier. Since looping over pixels is not a coherent mathematical approach whose complexity is easy to compute. Once it is expressed as a matrix multiply between to matrices we can directly use a formula to compute complexity. More importantly, GPUs work fast precisely because they can parallelize this matrix multiply (as opposed to parallizing various kinds of for-loop structures).

In this section, im2col in the source code—unrolls local patches of the image so that convolution can be expressed as a matrix–vector multiplication.

Let the

The valid convolution output (size im2col outputs a long vector that can be then transformed to an image on the other end):

We can express the convolution as a matrix multiply:

where

Expanded, the output entries are:

Loss Backpropagation in Convolution

1D Convolution Example

Let the 1D convolution be:

where:

- (

- (

- (

Assume a scalar loss (

Step 1: Gradient w.r.t Output

Step 2: Gradient w.r.t Kernel

Construct the input Toeplitz matrix:

Then the gradient w.r.t the kernel is:

Observation: Each kernel weight sees only the local patches of the input it touches, preserving locality.

Step 3: Gradient w.r.t Input

Again, each input element only receives gradient from the outputs it contributed to.

2D Convolution Example

Only for completeness, it should be clear that 1D and 2D is handled the same way using im2col

For 2D BTTB convolution:

with scalar loss (

- Gradient w.r.t kernel:

- Gradient w.r.t input:

Observation

- Each kernel weight is influenced only by the input pixels in the patch it was applied to

- Each input pixel receives gradients only from outputs it contributed to

- This is why CNNs learn localized features efficiently.

2D Fourier Transform Convolution as Matrix Multiplies

Similar to the spatial convolution case we will represent the Fourier transform as a sequence of matrix multiplies. The recipe is as follows,

- Fourier Transform of Kernel

- Fourier Transform of 2D Image

- Elementwise Multiply in the Frequency Domain

- Inverse Fourier Transform

These matrices can get quite huge, but I thought we need to see them explicitly to make understanding them a bit easier.

We assume:

Flatten row-major:

The 2D DFT matrix for a 4×4 image (flattened row-major) is:

Where

1. Fourier Transform of the Kernel**

where

Then:

Take the first row,

$$

\hat{W}1 = w{11} + w_{12} + w_{13} + w_{21} + w_{22} + w_{23} + w_{31} + w_{32} + w_{33}

$$

2. Fourier Transform of the Image

Take the first row,

$$

\hat{X}1 = x{11} + x_{12} + x_{13} + x_{14} + x_{21} + x_{22} + x_{23} + x_{24} + x_{31} + x_{32} + x_{33} + x_{34} + x_{41} + x_{42} + x_{43} + x_{44}

$$

3. Multiply (Elementwise) in Frequency Space

Define the frequency-domain product:

Written explicitly:

$$

\hat{Y}=

\begin{bmatrix}

\hat{W}_1 \hat{X}_1 \

\hat{W}2 \hat{X}2 \

\vdots \

\hat{W}{16} \hat{X}{16}\

\end{bmatrix}

$$

4. Inverse Fourier Transform

To return to spatial domain:

Explicitly:

$$

\mathrm{vec}(Y)

= \frac{1}{16}

F

\begin{bmatrix}

\hat{W}_1 \hat{X}_1 \

\hat{W}_2 \hat{X}_2 \

\hat{W}3 \hat{X}3 \

\vdots \

\hat{W}{16} \hat{X}{16} \

\end{bmatrix}.

$$

Thus the first row of the output looks like (the subscript is 11 because it will eventually be recast to an image),

$$

y_{11} = \frac{1}{16} \left(

\hat{W}_1 \hat{X}_1 + \hat{W}_2 \hat{X}_2 + \hat{W}3 \hat{X}3 + \cdots + \hat{W}{16} \hat{X}{16}

\right)

$$

We will try to focus on that first term on the RHS,

$$

\hat{W}1\hat{X}1 = (w{11} + w{12} + w_{13} + w_{21} + w_{22} + w_{23} + w_{31} + w_{32} + w_{33}) \times (x_{11} + x_{12} + x_{13} + x_{14} + x_{21} + x_{22} + x_{23} + x_{24} + x_{31} + x_{32} + x_{33} + x_{34} + x_{41} + x_{42} + x_{43} + x_{44})

$$

Compare this to

Eventually these two values will be numerically the same! We know this from the convolution theorem. In the next section we will see that the contributing values matter to the gradient back propagation and that is where the two approaches will differ.

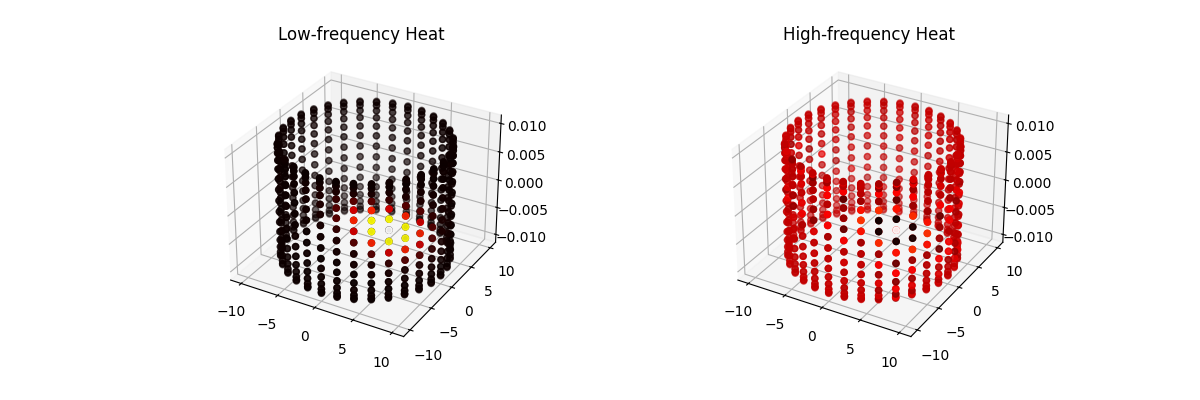

Gradient Comparison

FFT Gradient

Notice that every input pixel contributes to the gradient of

Similarly for other weights, EVERY pixel contributes to the gradient.

Gradient in the Spatial Convolution Case

Notice that each update depends only on the pixel patch that it touches!

Gradient update for scalar loss L

Computational Comparison

Spatial Convolution

Suppose:

- Input image:

- Kernel:

- Output:

Number of multiplications

Each output pixel requires

- Linear in number of pixels and kernel size.

- Memory access is local, cache-friendly.

FFT-based Convolution

Forward pass:

- Zero-pad kernel to size

- Compute 2D FFT of input and kernel:

- Elementwise multiplication in Fourier domain:

- Inverse FFT:

Total computational cost

- For small kernels

- Spatial convolution is cheaper for small kernels, which is why CNNs prefer it.

- FFT becomes advantageous only for very large kernels or very large images.

TL;DR

- Spatial convolution is efficient for small kernels and preserves locality which is crucial for CNNs to learn hierarchies.

- FFT convolution has global interactions, destroys the local inductive bias, and is only computationally advantageous for very large kernels.

Conclusion

We have seen that spatial convolution is not only computationally more efficient but also better suited to capturing the hierarchical structure inherent in most images. For instance, a face detection algorithm may rely on local patterns such as the triangle formed by the eyes and the nose. A kernel that focuses specifically on this local arrangement is highly effective because it preserves locality.

Conversely, in domains like recommendation systems, where data may be represented as a sparse matrix of product–user interactions, capturing global patterns can be more important. Here, the “local” interactions often correspond to users with strong connections, whereas broader, global patterns reveal trends across the entire system. In such contexts, FFT-based approaches—or methods that leverage global connectivity, like graph convolutional networks—can be more appropriate.

This contrast explains why spatial CNNs excel in image-based tasks, while GCNs or FFT-based methods are more suitable for graphs representing global interactions, such as those between users and products.

References & Further Reading

“A Beginner’s Guide to Convolutions” (Colah’s Blog) – A visual, intuitive introduction to convolution and receptive fields.

https://colah.github.io/posts/2014-07-Understanding-Convolutions/“The Fast Fourier Transform (FFT): Most Ingenious Algorithm Ever?” (3Blue1Brown video) – A beautiful geometric explanation of the FFT.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=h7apO7q16V0&utm_source=chatgpt.com“Convolutional Neural Networks for Visual Recognition” (Stanford CS231n) – Gold-standard material on spatial convolution.

https://cs231n.github.io/convolutional-networks/

Visualization & Signal Processing

Khan Academy – Fourier Series & Fourier Transform – Visual and interactive explanations of frequency-domain thinking.

https://www.khanacademy.org/math/differential-equations/fourier-seriesDSP Guide (Free Online Book) – Clear, practical engineering-focused intuition on convolution and transforms.

https://www.dspguide.com/

Implementing FFT-based Convolution

PyTorch FFT Tutorial – How PyTorch performs FFT-based convolution behind the scenes.

https://pytorch.org/docs/stable/fft.htmlSciPy signal.fftconvolve – Practical tool frequently used for 2D FFT convolution.

https://docs.scipy.org/doc/scipy/reference/generated/scipy.signal.fftconvolve.html

Graph Neural Networks & Spectral Methods

“A Friendly Introduction to Graph Neural Networks” (Stanford) – Excellent intuition about GCNs and why they differ from CNNs.

https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs224w/“Spectral Graph Convolution Explained” (Medium) – Gentle intro to graph Laplacians and filtering.

https://medium.com/towards-data-science/spectral-graph-convolution-explained-6dddb6c1c2b0

Practical Engineering Notes

“Why FFT Convolution is Faster” (StackOverflow discussion) – Short, practical engineering explanation.

https://stackoverflow.com/questions/12665249/why-is-fft-convolution-faster“im2col and GEMM: How CNNs Are Really Implemented” (DeepLearning.ai forums) – Helps connect the maths to real-world kernels.

https://community.deeplearning.ai/t/how-im2col-really-works/27659