Signaling, Skills, and Intellectual Health in the Age of AI: Thoughts from UChicago Career Conference 2026

Introduction

I was recently invited back to the MA department at UChicago for a career conference. Sitting there, listening and speaking, I found myself asking a rather uncomfortable question:

How much of what we value in education is pure signaling? Is this still true in the age of AI?

It is perhaps an opportune moment to recap the signaling model of education. In labour markets with asymmetric information, employers cannot directly observe ability. In Michael Spence’s signaling model, education does not necessarily increase productivity; instead, it separates high-ability individuals from others because it is less costly for them to acquire. In this paradigm, education serves as a “signal” of ability.

I think AI has changed this status quo because the cost of acquiring education has reduced to the point that there is no cost differential between high-ability and low-ability individuals for a large number of courses. To be more specific, the cost of sending a signal of education is reduced to the point of being indistinguishable between both groups. The cost of actually educating oneself is likely still lower for high-ability individuals, it’s just that sending this signal is easier.

This essay is intended to answer some of the questions that I recieved at the conference, some of which are outlined below,

- But what does “actually” educating oneself really mean?

- What does it look like? Which classes should I take?

- What should be the emphasis of my self-study?

- How do I position myself best for the job market?

Beyond The Signal: So What Should I Study?

In the old (read: pre-AI) world where education was largely signaling, I think taking classes that superficially but with high probability signaled education, such as cloud skills, basic Python programming, and machine learning applications, were good enough. But in the new world, the cost of acquiring these skills is zero. Thus high-ability individuals need to seek out higher difficulty tasks that are relatively lower cost for them to acquire in order to send a strong signal. Mathematical maturity, comfort with abstraction, and disciplined reasoning are not signals in themselves; they are capabilities that affect what you can build, debug, or invent.

Thus class choices should reflect these core values:

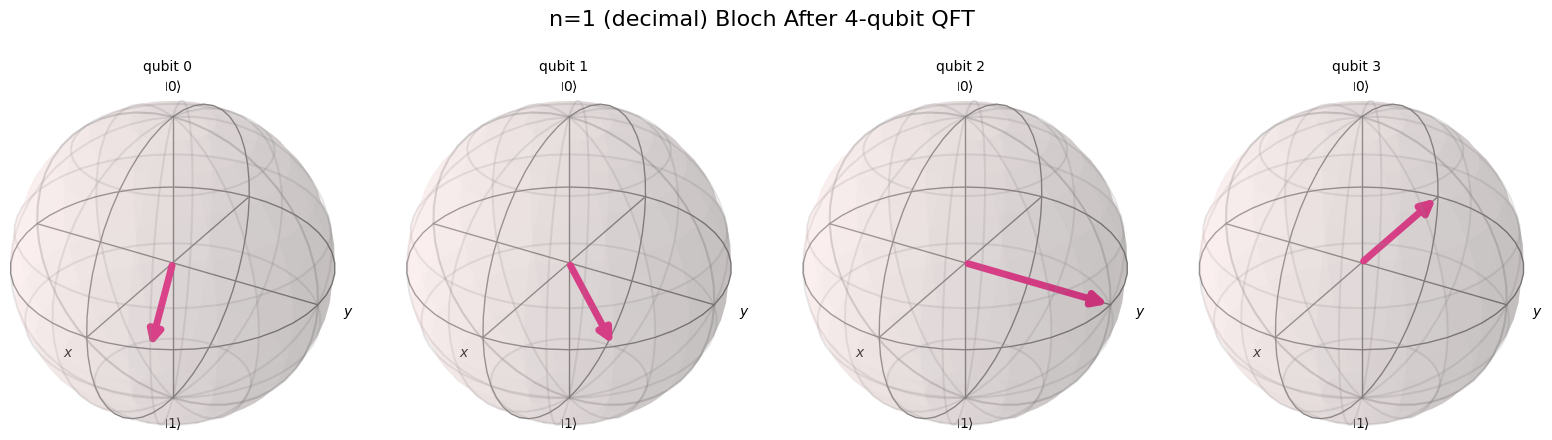

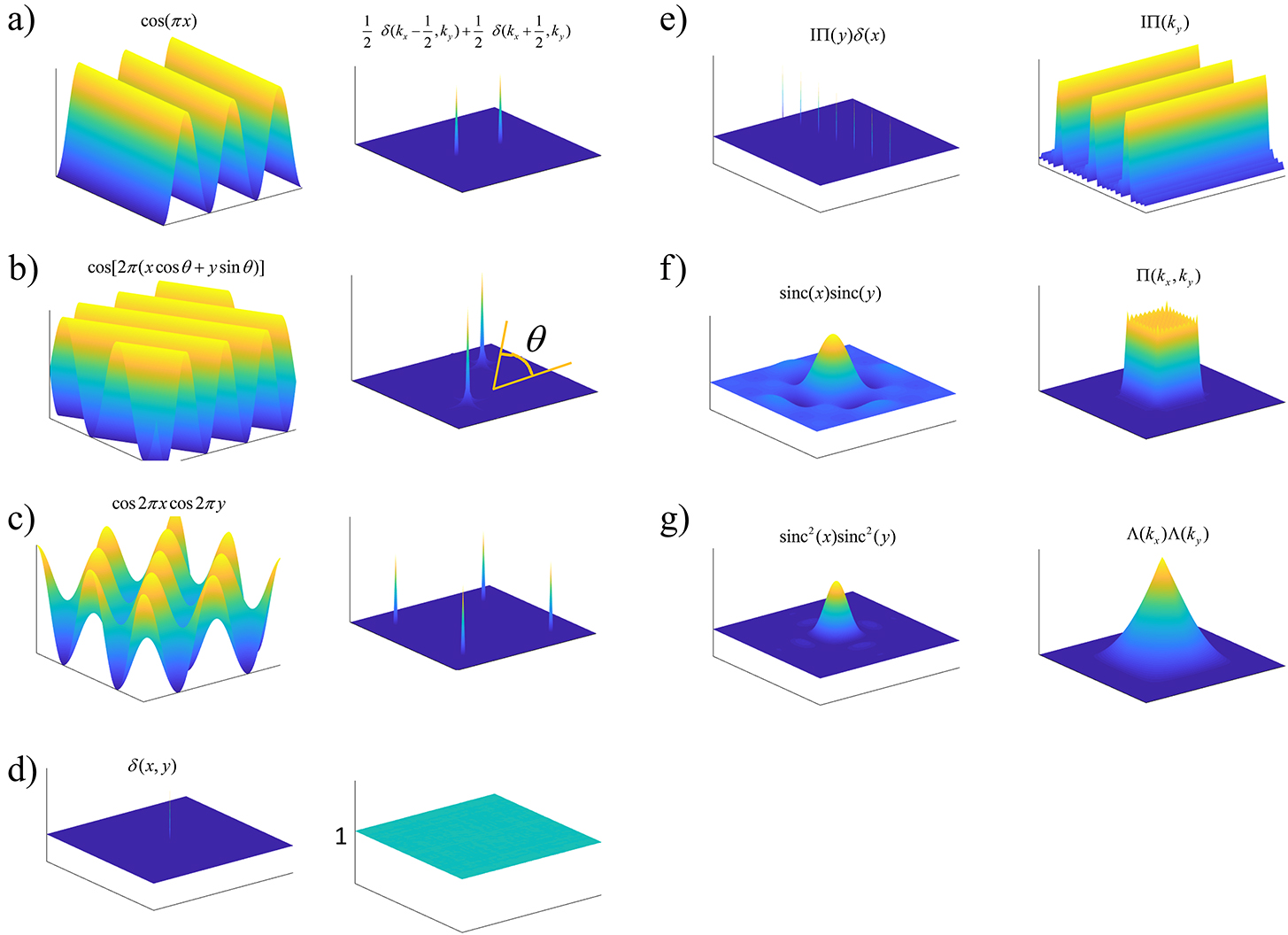

Mathematical courses that emphasize the core mathematics that make up machine learning, such as linear algebra and differential equations

Looking under the hood of machine learning, focusing on the mathematical fundamentals of machine learning

Social sciences courses that challenge your world view and force you to think about what the world should look like (more on this below)

Good Intellectual Health

More important than ever, and not specific to tech jobs but just life in general, is maintaining good intellectual health.

Reading books both in your field and outside of it is now more important than perhaps in the world before AI. Using AI increases one’s distance from one’s self. One’s ideas and one’s thoughts are now further than ever from one’s own experience. Reading books and writing reduces this distance. Since idea generation and critical thinking depend so heavily not only on the final output but also on the process by which one reaches it, exercising this muscle is now more important than ever.

Maintaining good intellectual health, however, is almost entirely self-policed. There are very few reliable ways to monitor how much AI shapes one’s own work. What usually starts as submitting homework in a rush can escalate to generating entire essays using AI, the slope is truly slippery. One cannot afford to replace the cognitive effort that builds depth, originality, and judgment. Only you can decide if the level of AI use hampers your intellectual health, and only you can feel its effects.

Emphasizing the Social Sciences

The sciences are exceptionally good at helping us understand what the world is. As a result, advice about improving technical skills tends to be prescriptive and measurable. The social sciences operate differently. They help us think about what the world should look like. They force us to articulate assumptions about behaviour, incentives, norms, and institutions. The process of forming a view about what the world ought to be is central to intellectual health. It requires reflection, judgment, and an awareness of values, not just optimisation. Admittedly, this is difficult advice to give at a career conference for students focused purely on technical roles. The impact of studying sociology, psychology, or economics is harder to measure in a tech performance review. It doesn’t map cleanly onto a skills matrix. But it is no less important for that reason. The social sciences implicitly construct world models. Whether in sociology, psychology, or economics, they offer structured ways of thinking about how systems of people behave. That kind of world-building is essential for understanding where highly parameterised models, such as those produced in machine learning, actually live. Models do not operate in a vacuum; they operate within social and economic systems.

This becomes even clearer in business contexts. Firms operate with explicit views of what the world should look like, in terms of acquisition, churn, retention, revenue. Machine learning systems are deployed inside those normative visions. I admit there is something slightly distasteful about motivating the social sciences purely in terms of churn or revenue. It feels almost sacrilegious. But in practice, those incentives shape the environments in which technical systems are built. And if that were not the case, the audience at a career conference might be asking very different questions, comrade.

TL;DR;

The “sticker” value of UChicago’s education has held steady relative to other similar institutions. It might even have appreciated slightly. However, the absolute “sticker” value of education as a signal of ability in top schools (and indeed everywhere else) has gone down. Thus the onus is now on students to take courses that more appropriately signal their ability, not just in purely technical terms (such as mathematics, physics, machine learning) but also in critical thinking terms (such as expertise in the social sciences). The days of superficial knowledge that use model.fit(X) are over.

The UChicago brand will likely hold its value for years to come but it is not going to be enough. Even though the bar to have superficial knowledge is lowered thus muddying the difference between high and low skill individuals, the bar to have truly fundamental understanding of the sciences including (and perhaps especially) the social sciences is has never been higher.